The backend failed.

XID: 84283847

Varnish Cache Server

We take a look at some highlights, middle and lows of Scientific American’s history, with former editor John Rennie.Astrophysicist Alan Guth also appears in one segment.

This is the Scientific American Scientific Conference, published on August 29, 2020.I’m Steve Mirsky.Se are 175 years old of the publication of the first factor of Scientific American.Our existing factor, the September factor, examines the history of the magazine, from the content to how the use of words has replaced how the gaze has evolved, and in this episode of the podcast :

[CLIIP DE RENNIE]

This is former Scientific American editor-in-chief John Rennie, who gave a lecture in 2008 to a New York skeptics organization that entered a component of our history.I’ve also prepared a segment on some of the stupidest things ever done.1845.And we will also hear a segment sponsored through the Kavli Prize with the mythical astrophysicist Alan Guth.First, a component of John Rennie’s lecture, part of which aired in an episode of Science Talk in 2008.

John Rennie:

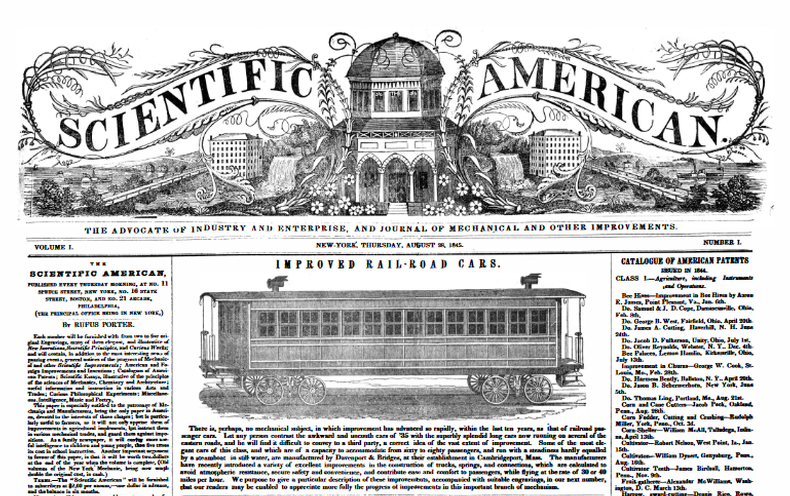

Scientific American has been around since August 28, 1845. It was only 4 pages long, 4 giant pages like a newspaper; there were a lot of old patent ads and poecheck, and there were little scientific reports and all sorts of things about itArray … But, you know, being there since 1845, it’s obviously very long. This necessarily considers the beginning of the commercial revolution of the moment. It was before the civil war. It is so early that we know that Thomas Edison read it as a child and we know that Thomas Edison read it as a child because he came to the publishers’ offices and told them when he demonstrated his invention of the phonograph for the first time. It’s been around since 1845, I mean Scientific American has been around since before airplanes, since before automobiles, since before X-rays, since before relativity, obviously. It has been around since the discovery of electrons; the germ theory of disease has existed long before. It’s been around for a long time, but it’s nothing but bullshit and it’s something that, on some level, the writers and editors of Scientific American have dealt with in this long history, so I’m going to go through to show you some highlights. , or weak issues, as the case may be, from Scientific American’s experience in this matter.

The heyday of Scientific American’s involvement with something akin to skepticism literally dates back to his late teens: 1920; because this time Scientific American was involved in several other projects that were aimed at checking to discredit various things whose clinical accuracy was questionable. One of them referred to an entire area; A very critical look is taken at other spaces of medical charlatanism and, for this, this is perhaps one for which they are probably best known. How many of you have heard of Abrams [ERA] electronic reactions? Probably not too much. It’s not very well known these days, believe me. However, at the time, in the early 1920s, it was one of the top fitness fads sweeping America. It was founded by Dr. Albert Abrams, who proposed this radiological technique to diagnose and ultimately treat disease, and it was so compelling, it was so enjoyable to many in the United States that it has really started to convince other physicians. . and the AMA began to see it as a major threat; and they were making their own efforts to verify and prevent the spread of ARD. And Scientific American was hired to verify and help debunk that as well, so let’s start by just talking about ERA. It turns out that Dr. Abrams discussed something around 1916; He turns out to have had this concept from a diagnostic technique that referred to a device he called an energizer.

This is the magic of how ERA works. With ARD, the patient would give a blood pattern or it could just be a pattern of just about anything. Over time, it started to become so liberal that it went from blood or other physical fluids to the point where Abrams said you can only write by hand or just take pictures of people, and they will be taken. Then the energizer wires would succeed and connect to a healthy user, who would have to face west, because that was very vital, and they would hold those things here and tie the others. cables as needed. and then the practitioner would come and (pat sounds), feel the abdomen of this controlling user and pay attention (pat sounds); And from the sounds, you may find out what was wrong with the user who gave you the blood pattern because, you see, it will be scientific. So some of you might need, I guess, [if] you ask me to repeat it, I’ll do it, because it’s so complicated. The electronic resonances related to Adam’s ill health would migrate up through the wires and adjust the electronic resonances of that user, so the practitioner could then pay attention to him and him.

Now why didn’t you come by and pay attention to the person in poor health? Actually, I don’t know, it’s not even clear; however, that was wonderful because Abrams was promoting those boxes for around $ 400 to other people who [we] would be allowed to become new PLAR practitioners and the wonderful thing was that that component of the license was that you didn’t have any. explanation of why they were allowed to open the box and internal gaze. (Laughter) You may never look inside the box. And then, you know, he was promoting it, he was also promoting other kinds of seminars back then, training other people on how to use the devices; he was minting money. He made millions of dollars in the early 1920s, which was a considerable amount of money. Oh! And this along the way: not only did you prevent with the diagnosis, but you also moved into the realm of the remedy because of course, if you can use those resonances to diagnose what is wrong, reversing the polarity in the use of a device called Oscilloblast, which is a kind of opposite energizer, he can write the resonances correctly and fix what was wrong with you. And it was amazing.

I mean, after a while, I was just solving almost anything with him and was even used, at one point, to identifying where other people might be.I mean, Abrams at one point didn’t warn before taking an image of someone and using their energizer to look at a map and figure out where that user might be.Can you believe why the idea of the fitness government was to prevent courage?So Scientific American intervened and embarked on a nine-month investigation into the ERA, in which they thoroughly and thoroughly reviewed all the claims and addressed them as they were; it was a style of research, because they essentially said, “Okay, Abrams wouldn’t cooperate with this, Abrams didn’t need anything to do with it, but Scientific American discovered a practitioner who was willing to cooperate: Dr. X, as discussed in the magazine at the time, and Dr. X would consent to it.”And then Dr. X said, “This is how ERA works, this is what “Array and the Scientific American organization in combination” is meant to do then say, “Ok, if that’s the case, let’s look at this.”

So they started with this big check, in which they gave the ERA practitioner, Dr. X, they gave him a series of natural germ cultures in control tubes and essentially said, “So here it is, it is the purified causal agent of these; it’s labeled, just tell us what it is.”Because if you can definitely diagnose if someone has, for example, syphilis in their frame from this blood pattern processing and if we give you a natural germ culture, you definitely deserve to be able to identify them that way.And Dr. X agreed it was a smart check, and then he implemented it and the effects were amazing, because the effects were that he hadn’t passed the check.’one of them; everyone misunderstood, regardless of what you might have imagined, that only [by]] possibility would you have idea that I would have succeeded in some of them.Well, Dr. X didn’t take that mendacity away, because he looked at him and said, “Oh!Here’s the problem. You see the labels you wrote, some have red ink, yet the redness of the labels interferes with the resonance.”

So they replaced that and continued to do so. They continued to do this over and over again, month after month.Every time they tried it and [the ERA] failed, there was some kind of excuse and they corrected it and would make it come back and start over and over again And, despite everything, they were given to the point where they discovered a blaster one way or another, and they just broke it and looked inward and decided that the internal reinforcement was , as you probably would have imagined, a whole rat’s nest made of wires, and in some cases they didn’t look like anything.It would seem complicated, even if you took a look inside.Some of them don’t even connect to external wires in this thing.

So, after nine months, Scientific American, in spite of everything, has come to its own conclusion about all this and its verdict, and this was part of a much longer article that denounces all of this, however, as you can see, was essentially saying: “This committee discovers that the claims made in the convening of Abrams’ electronic reactions and electronic practice in general are not justified and we believe they have no basis for fact.In our opinion, so-called electronic reactions do not occur and therefore – so-called electronic remedies are worthless.”It was a style example of some kind of thing that I think [we’d] like everyone to see, when it’s imaginable to take some kind of medical chatter and take it to a smart skeptical review at all times.

Scientific American has not been as successful in this regard. Because around the same time, another set of things that worried him was pursuing the spiritist movement. Spiritualism [was] very, very big back then – there were a lot of sessions going on – and Scientific American started a festival where they essentially promised two prizes of $ 2,500 to any non-secular medium that could simply demonstrate certain things, to be able to Demonstrate a physical manifestation to the satisfaction of the Board of Investigation or could otherwise, I think, simply show other evidence of it. And they’ve been going for months after months, literally years, hunting down other mediums and just, you know, blowing them up. Harry Houdini was part of the team that would travel with Scientific American. I don’t think Arthur Conan Doyle was really a component of this, because, of course, he was a little comfortable with the issue of non-secularism, but he was also very concerned about that, and there was an editor, Malcolm Bird, who was – wonderfully appointed. , Malcolm Bird – who was the editor of Scientific American at the time, and it’s pretty transparent when you reread the accounts they wrote about their attempts to derail those various sessions, that Bird was quite sympathetic to the spirit cause. It was quite transparent that in many cases it literally sought to locate a ghost in some of them; However, the chart that they put together, the panel that they would send to the one-time sessions never, you know, found out what they found: they kept locating fraud after fraud.

However, this all came to a head when he ended up investigating the case of a celebrated non-secular medium whose name was Mina Crandon, although she was sometimes called Margery. It’s become kind of a downfall of Scientific American’s anti-ghost crusade, because Margery was, you know; she would have those various meetings where she would supposedly show amazing things and it would turn out that she had an incredible touch with the spirit world, through Walter – Walter, who was the male voice speaking through her at the time. People were literally, literally inspired by the paintings he was doing and supposedly now that’s something that I get directly from Penn Jillette himself, because when he was telling the story at the amazing reunion last year, Penn Jillette was really able to explain it. This is because she had met and interviewed Mina Crandon’s granddaughter and the granddaughter was able to verify a few things: Mina was something of a spectator, especially through the weather, and supposedly did many of her sessions nude. (laughs) Maybe that kind of relief eased the skepticism (laughs) that was related to that and that might have really affected [the investigation]. When the Scientific American research team appeared and began living in the Crandons space in Boston, Malcolm Bird was paralyzed by Mina; he thinks she’s cool.

When you read those accounts, he firmly believes that despite everything, despite everything he has discovered the original article, and again, I would only quote what Penn Jillette told me about it: that apparently, according to the little boy. -Margery’s daughter, yes, she was actually sleeping. yet, which was convenient, however, not for Scientific American. Because Scientific American was on its way to winning more than $ 5,000 in prizes. But then he was in a position to do it, when Harry Houdini, who was actually a member of the team, was not there; he was out on a hike and found out. He was reading that it looked like Scientific American was in a position to do it, so he rushed over so he could be there for some other consultation that everyone was concerned about, and he is there for the consultation. He’s very disappointed that Malcolm Bird and other panel members seemed to be in a position to characterize him, and in the middle of the query at one point, Harry Houdini, flees [jumps] to his feet and shows evidence of tampering, and he’s denouncing her right in the middle. And Malcolm Bird comes back [jumps] to his feet and begins to vigorously protect Mina’s honor, which brings me to what feels like a fist fight then (laughs) that broke out between Harry Houdini and Malcolm Bird; and I think it’s probably overkill in my mind’s eye to imagine [the match] spilling out onto the streets one way or another, because I really can’t believe that in a match between Harry Houdini and Malcolm Bird, it would last a long time. . However, that was enough to pretty much destroy Scientific American’s ghost fighting attempts at this point. So we never distribute the $ 5,000 in prizes. Hurrah!

Steve Mirsky:

John Rennie was the seventh editor in the history of American science.Now he’s at Quanta Magazine.This is my wonderful chance of being at SciAm during his tenure, as well as his successors, Mariette DiChristina, now dean of the Boston School of Communications.University, and Laura Helmuth, recently arrived from The Washington Post.

Alan Guth is also part of scientific american’s history.In 1984, he and Paul Steinhardt published a founding paper entitled “The Inflationary Universe”.Here’s a short segment of about six minutes with Guth, through the Kavli Prize.

[GUTH KAVLI SEGMENT]

In 2009, Guth participated in a roundtable at the annual assembly of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.I presented the highlights of this roundtable in this podcast.Just take a look at portions 1 and 2 of the “Stars of Cosmology”.”to have his mind and that of his colleagues on the state of cosmology.

In 175 years you make some mistakes. And in the magazine’s existing factor, the September factor, there is an article that puts our feet in the fireplace on some of the most mistakes this publication has made in the last 175 years. I, on the other hand, took a few minutes to study some of the fewest mistakes we’ve made in the last 175 years.

In 1846, we shared a terrible concept of ship propellers.”In fact it’s surprising,” we wrote, “that the men of capital in England persist in remaining so completely ignorant of the undeniable philosophical precepts of mechanics, to the point of assuming that a propeller in any way in the screw precept can rival the screw precept.undeniable Fultonian wheels.” What we missed was that when a shipment rolls, more than one aspect of the paddle is submerged, so that aspect produces more power.The resulting orientation challenge is just an explanation for why today’s lack of pallet carriers. Our original edition of the propellers was obviously a bad rotation.

In 1869, we had concepts for a better way to get between Manhattan and Brooklyn than through a suspension bridge.”JWMorse has designed a bridge that allows a much lighter structure than a general suspension bridge and is therefore much less expensive for Mr. Morse’s task is to transport himself across the river to a giant platform, suspended via wires to a cart that rolls on a porch across the Array River …the fact that the traveler hangs only 3 feet above the water – and therefore almost at the street level, facilitates the crossing of the river through heavily loaded carts, and will also be appreciated through the painter who returns on foot from home after a hard day of paintings in the factory or warehouse.As far as I’m concerned, if there’s anything, worse than being 130 feet above the East River, it’s three feet above the East River.

As he heard from John Rennie, Scientific American in the 1920s was excited about the demystification of query holders who claimed to speak to the dead.But in 1923, we argued that some psychics, not “the flagrant fraud that defrauds widows of their insurance cash through “messages’ from their deceased husbands” – to be paid for their services.”After all, even a medium will have to live.No one has ever advised that the doctor have a job, next door, as a carpenter or hack driver, gain a live with him and give him time to lose the cure of the disease …the medium, to the other people he serves, provides a service as genuine as the doctor …Why ask him to give it away for nothing? A century later, here at Scientific American we are all short of generosity, even average.

We were also not involved with our own income, at least in 1849.In May of that year, we apologized to readers for bombarding them with two columns and a portion of ads.In the total act. In 1915, we took an inventory and explained a position we still maintain: “The time and growing importance of advertising in fashion journalism have replaced this encouraging attitude.

It’s 2020 and we don’t have any flying cars yet. (And if humans’ ability to drive on the floor is a clue, thank God.)But in 1915, we were anxiously waiting for transparent aircraft: “The army government is ahead of the progression of the new French invisible aircraft Array.. aluminium], instead of canvas, stretches a transparent material …called “cellon” Array … a chemical mixture of cellulose and acetic acid.Almost the same transparency as glass, it does not crack or crack and has the tenacity and flexibility of the rubber.Which is true. And that’s why it’s now used for eyeglass frames.Of course, we can’t say with certainty that there are no invisible French planes.

In 1913, we reported the discovery of the fossil skull of the so-called Piltdown Man: “A Piltdown Common, Sussex, England, an English paleontologist, M.Dawson discovered, about a year ago, a fairly complete Huguy skull representing the oldest relic of the Huguy race in the British Isles, and one of the oldest discoveries in the world.And two years later, we conducted clinical research on the discovery, through Professor WPPycraft of the British Museum.In this piece, titled “Huguyity in process: the direct ancestor of the fashion boy and his appearance,” Pycraft wrote: “Although the skull is necessarily huguy, that is, it is the skull of a member of the genus Homo, representing a low-ranking boy, the jaw, on the other hand, as we have already noticed, is almost that of a monkey.Piltdown Man eventually turned out to be a hoax, consisting of parts of a huguy skull and an orangutan jaw, when Pycraft said the jaw was “almost that of a monkey,” he was almost right.

Finally, in 1883, we thought that no one would need a telephone: “Although recent experiments have shown the option of telephoning through long circuits, it is doubtful that the tool will be used otherwise than localArray …there is no sign formula like Transparent as the existing Morse code, interpreted through the sounderArray..through the telephone, it is the sound of a word and not its vowel and consonants that the operator receives and an error can occur smoothly even in the most productive conditions.”Well, yes, that’s why the game is called a phone.In fact, even though everything had gone well, with the advent of texting, it is said that many of us prefer those mini-tweagrams to those.As the Gary Gulman comic said: “For me, the phone is an app rarely used on my phone.”

That’s it for this episode, get your clinical news on our website: www.ScientificAmerican.com, where all our policy against coronaviruses is the paywall, which you can get for free.

And stay with us on Twitter, where get a tweet every time a new article arrives on the website.Our Twitter call is @sciam. For the Science Talk at Scientific American, I’m Steve Mirsky.Thank you for clicking on us.

Follow us

American Arab Scientist

You still have loose pieces left.

Support our award-winning clinical and technological advances.

Already subscribed? Connect.

Subscribers gain advantages from a more rewarded policy of clinical and technological advances.

See subscription options