Only through the relentless crusade to commemorate Peterloo’s bloodshed has this abbreviation of violent state repression become so widely recognized. I have lived most of my life in Manchester and yet in my past adolescence before hearing the term and can say to revel in that I am far from the only one.

We have the recent statue of Emeline Pankhurst in St. Peter’s Square, opposite the tram of the new Peterloo Memorial. We have much older memorials for radicals, of course. In St. Anne’s Square, Richard Cobden triumphed in bronze. A few hundred Meters from Cobden, we have the solemn figure of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln, the emancipator. This statue of the president was delivered through Ohio philanthropists in 1919, officially to commemorate the self-sacrifice of Lancashire cotton workers during the American Civil War, who, in a letter to the president, suggested Lincoln continue his blockade of southern ports, starving the southern U. S. economy and personnel in northwestern English. Lincoln responded with his own public letter.

There is a fresco that connects those two men, whose absence, and presence, is the passive erasure of blacks from the history of our country in one word: if the Bronze Cobden left its base, it would look to its left and head towards Holland

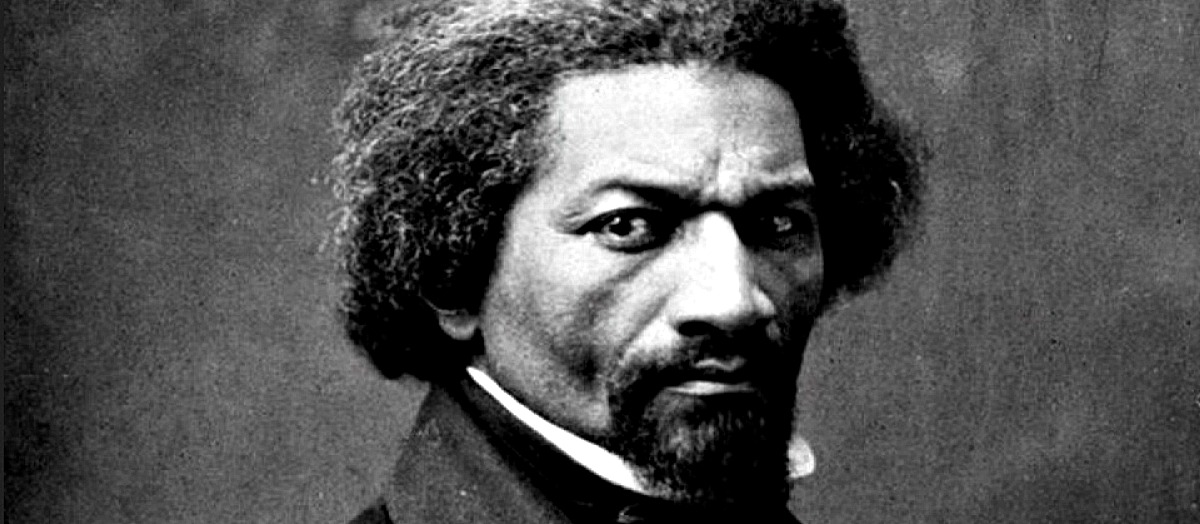

Frederick Douglass was born a slave in 1818, according to his own calculations (the birth of human furniture does not value as it should be recorded), in Tuckahoe, Maryland. He escaped on 3 September 1838; that date, he chose his birthday.

It is highly unlikely to put here the ordinary nature of this person. We are fortunate that he took the time, when he was a slave child, to borrow an education based on the literacy of some of the loose neighbors, that is. . white children, which prompted them to teach him letters of the alphabet that he did not know. He used it to examine his first illicit book; The Colombian speaker wrote his first autobiography, An American Slave’s Tale of Frederick Douglass, in early 1845, shortly before arriving in Britain as an agent of the American Antislavery Society. There have been several updated editions in the long life. Douglass, the last in his 70s.

When Douglass arrived in the north-west of England, he was already known in abolitionist circles, of which Cobden was a member: the wonderful young fugitive who once had to fight a ‘black’ ‘breaker’ named Covey and who had never submitted. be returned without retaliation. An extremely brave position to take. But he was more productive known for his wit and language, the things he appreciated himself above all else. In England, Cobden, with John Bright, was his first contact. He wrote about his stay with Bright at his home in Rochdale, and became Dada his eventual apartment in St Ann’s Square, most likely Douglass spent time with Cobden in his city on the corner of Byrom Street and Quay Street. The space remains state and is commemorated through a plaque.

Douglass attended Parliament with Cobden. Obden, one of the founders of the Manchester Athenaeum (now a member of the Manchester Art Gallery), to which Douglass gave at least one lecture, and gave at the final assembly of the Anti-Corn Law League with Cobden and Bright on 2 July 1846.

Douglass remained in Britain for nineteen months on that first visit. The only addresses we have for him at this time are in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester and London. Only London is commemorated in some way. During his tenure in Britain, Douglass was still a slave. He had learned from Boston that the agents of Thomas Auld, the guy who claimed it as property, had been noticed in the state. Some of his friends in Scotland paid the cash to buy it and eguiparlo, a contentious factor that we can read in this letter, written, as shown at the return address, at 22 St Ann’s Square, Manchester, England, 22 December 1846. “

When Lincoln nevertheless made the decision to turn the Civil War into a war to end slavery (this was not his original intention), he appealed to Frederick Douglass in particular to recommend and assist him, that is, in the enlistment of black Americans in the Douglass he was entirely in favor of this, provided that they were admitted on an equal footing in all respects. They were given insurance and Douglass appealed for weapons for the first two “colored regiments” (in which his two sons enlisted). The men who enrolled, many of whom were fugitives, were assigned to duties of commissioner and abandonment, unarmed, in other uniforms, with a lower salary. Lincoln then asked for his help filling out other regiments and Douglass refused. He refused in writing. He also went to Washington to submit his user complaints to the President of the Union.

Shortly after this assembly at the White House, the men, women and young people working in the cotton generators of north-west England took the collective resolve to refuse to weave any Confederate cotton that managed to end the blockade. They did so knowing that this meant abundant relief at work, wages and probably deprivation and famine. However, they sent Lincoln a letter from “The Working Men and Women of Manchester” ingsing him to continue the blockade and despite the slave. It should be noted that the answer, though honest and grateful, was addressed ” to Manchester’s staff. ‘

Just before Douglass’ death in 1895, Ida B. Wells, a civil rights employee unknown to the public and having lynchings in the United States since the post-reconstruction period, was traveling in Britain. This woman, with an incredible point of fact of courage and resilience, surely pledged to fight for the civil rights of African-Americans and especially for the right to vote for African-American women after Susan B. Anthony left his cause. Wells visited the same locations in the northwest: Manchester, Rochdale, Bury, Salford, Stockport, Ashton, Moss Side, as did Frederick Douglass, Henry Brown, George Washington Williams, William and Elizabeth Craft, and many others before. Manchester in Wells’ case) were searched and registered through Hannah Rose for their website. This thoroughly researched resource documenting the presence of these men and women in Manchester deserves n Not as mandatory as it is.

This is not a proposal about who deserves and deserves not to be called back publicly, however, now that this absurdly expected verbal exchange is despite everything that is happening, we can begin, in Manchester, by hitting a statue of Frederick Douglass. next to Lincoln and rename it Douglass Square. This area may include monuments to Ida B Wells, Henry Brown and others who fled slavery or oppression and sought Manchester, not only, but specifically. It can also be an area to recognize Robert Rose, a 19th-century Manchester poet from the West Indies, as well as Sylvia Pankhurst, Ellen Wilkinson, Lemn Sissay, among many others Manchester deserves to be publicly proud of; that long-term generations will be proud of, if given the opportunity to do so. It would not be a repudiation of Anglo-American relations, but a recognition of relations between all of us, and not reserved for heads of state.

It also deserves to be taken into account the date of this statue of Lincoln, 1919, which embodied the edition of America that America wanted to project: slavery and the racial department were over, and Honest Abe ended it. around the same time that most American Confederate monuments were erected and American imperialism began to develop. The statue of Lincoln will have to remain, but not as a commemoration of Manchester for Lincoln’s cause. This statue is there because Manchester staff have selected to threaten their own survival rather than help a particular economy committed to maintaining slavery for men, women and young people like Frederick Douglass, Ida B Wells, Henry Brown, George Washington Williams.

The physical manifestations of the soul of a city count. Recent additions to Manchester’s social history – the Turing Memorial, the Emeline Pankhurst statue and the Peterloo Memorial – are prominent for their isolation from the faster expansion of glass cathedrals to capitalism, are offering at least more shade for capitalism. The city’s vast homeless population.

Frederick Douglass has become one of the most prominent and outstanding men of the 19th century and the ultimate photographed user of the century. There are more lithographs, daguerreotypes and photographs of Douglass than Queen Victoria. It is a history lesson that we have selected not for as a city and as a society. To begin the process of relearning this story, let’s begin with the commemoration of Frederick Douglass.

David Whitham is a historian in Manchester, United Kingdom. Email: david. w@rngroup. co. uk

SUBSCRIBE TO THE COUNTER-CURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER

Comments are closed.

Share: WhatsAppFacebookTwitterTelegramRedditEmail This article is based on the 25th Chandrashekar Memory Conference on September 20, 2020. La original conference was given in Hindi and the occasion was organized through Punashcha, the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and Koshish. Friends, comrades accumulated here; I am very honored to have been invited to speak this year’s Chandrashekhar Memorial Conference, but I cannot [Read more . . . ]