Supported by

By Rory Smith

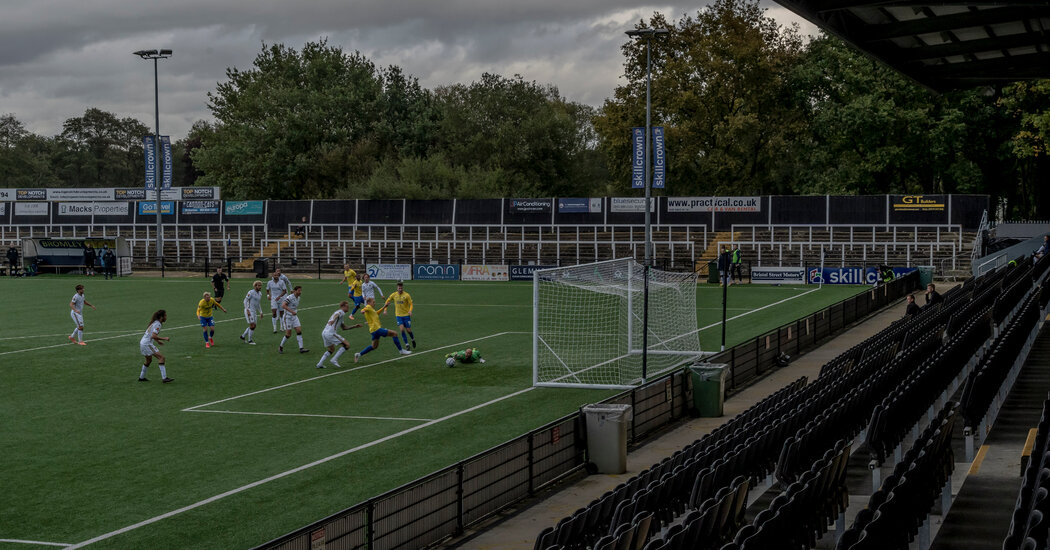

LONDON – Two football matches were held this weekend on Hayes Lane, a compact and orderly stadium in a quiet corner of south-east London. The first, on Saturday afternoon, took place in the silence of the game in the midst of the pandemic. As in the Premier League, enthusiasts were able to attend when Bromley FC, the team that holds the position, faced Torquay United in the fifth position of English football.

On Sunday, the other occupant of Hayes Lane, Cray Wanderers, will play. Cray is headquartered in a few divisions under Bromley, its owner for more than two decades. Most years, its games attract only a few hundred fans. London’s oldest club, ” said Sam Wright, his general manager. “We may also have older fans. “

Wright hoped this weekend would be different. In the absence of Premier League games on television, thanks to a stop abroad, he expected up to 500 fans. In the end, the crowd was only 357 people: more than Cray would have attracted, but still, as Wright said. it’s “pretty disappointing. “

However, the fact that two matches in the same game may take place on the same weekend, in the same stadium, and in accordance with disparate regulations, indicates the confusing and contradictory maze of regulations and restrictions that marked Britain’s attempts to curb spread. . coronavirus.

After a summer in which Prime Minister Boris Johnson encouraged the British to “eat in restaurants to help” the hotel sector he suffered, the government has undergone a radical change in recent weeks. Last month, after weeks of telling workplace staff it was time to resume on their daily commute, the government reversed course, ordering them to keep running away from home as much as possible. Then, having first ordered pubs across the country to close an hour earlier than normal, the government ordered the government on Monday to close completely in Liverpool, the city considered the ultimate threat of coronavirus spread.

Recently, last week, Johnson encouraged others to move videos to task losses. This week brought a new formula of three levels of localized locks, with several cities, basically in the north of England, now passed by strict socializing limits, and some corporations have been ordered to close completely.

At the same time, several indoor art venues in London, including the Royal Albert Hall, the Royal Opera House and the O2 Arena, have announced their goal of reopening this winter in front of a socially remote audience. remains forbidden.

The perplexity felt by many in recent months would possibly have been more productive summarized through television presenter Philip Schofield, who pointed out to Health Secretary Matt Hancock that lately it is legal to circulate with 30 adults to hunt ducks, but it is illegal. to reach up to 30 young people to feed them.

Nowhere, however, is the Kafkaesian inconsistency of regulations more evident than in football, where the stage is so complex that even those who will gain advantages, such as Cray’s general manager Wright, call it “ridiculous. “

Currently, the regulation looks like this: all so-called elite matches will have to be played without amateurs. National League North and South, divisions with a combination of professional and semi-professional teams.

Below, in the stretches of squats, not football leagues, enthusiasts are allowed, but still, the number of allowed varies from league to league, in some cases the limit is 350 and in others it can reach 600. they are not similar to local viral infection rates or the severity of regional blockages, but to a singles formula, depending on the length of stages in each league.

Things get even more complicated when groups from other leagues and grades compete, as they do in the early rounds of the FACup. When an elite ranked team is home, it is not allowed. Please note that only locals are allowed. If two non-elite groups compete, local and outdoor enthusiasts can attend.

As stated on one team, Corinthian Casuals, the regulations give the impression that “the coronavirus is smart enough to distinguish” enthusiasts from elsewhere.

The biggest challenge with the network of regulations and diktats, however, are all their holes. Jeff Hutton, Bromley’s executive chairman, doomed to play without enthusiasts, said his club was focused on how to lessen the monetary damage caused by the game in “We’re having a hard time starting the game, managing a live stream, and paying players,” he said. The British government has pledged grants to assistance clubs such as Bromley (several Premier League powers have recently submitted their own plans). cash has not yet been paid.

At the same time and in the same place, Cray reports a sudden rise in attendance. “We’re the highest point you can see right now,” Wright said. “On a day like Sunday, when there is no Premier League on TV, we hope to be a draw.

“It turns out that, given the situation, it’s useful for us as a club. “

Altrincham’s men’s team, in the same league and therefore on the same boat as Bromley, also suffers from only promoting a live broadcast of matches to some 750 fans, who welcome several thousand people into their stadium. “But our women’s team is entitled “to the crowd,” said Bill Waterson, co-chairman of the club, pointing out other nonsense in the rules. “The same goes for Manchester United’s women’s progression team, which also plays here. It wasn’t an idea. “

There are stories across Bishop’s Stortford F. C. he has a stadium with Enfield: the first has six hundred enthusiasts in his games, and right now only a little over half. The same goes for Radcliffe and Bury AFC, groups that play in the same place north of Manchester but on other levels. .

And at a time when millions of enthusiasts can’t watch their clubs play on the user, however, they’ve been told to move on to the videos and maybe they’ll also buy a price ticket for the Royal Albert Hall, there are many groups on the same wave as Cray. .

In south-west London, the Corinthian Casuals have seen a resumption of their audience since the start of their season last month, driven by big group enthusiasts who took the only chance to watch live football in person. Enthusiasts from groups like Brentford and Fulham come,” said a club official. “We’ve detected a trend in that direction. “

In the northeast of the city, Walthamstow F. C. had his greatest assistance “in 30 years,” according to Andrzej Perkins, the club’s head of communications. “We probably wouldn’t be batting three hundred in each and every game, but it’s been amazing for us,” he said. attended his first football match. It’s local, it’s outside, you can stretch and there’s not much to do.

Keith Trudgeon, the head of communications at Stalybridge Celtic, an unarmed pillar founded near Manchester, showed that his team also “above last season’s average. “But he said the effect is not as pronounced as it could have been because there are so many stalls to watch diminish the football league in the area.

“It’s a bit like a home,” Trudgeon said. “Only one of them, Curzon Ashton, is absent: he qualifies as an elite team, so he is not allowed to receive fans.

Trudgeon, like many, is governed by rules. Stalybridge has the largest stadium in his league and is convinced that the club can safely accommodate more enthusiasts than is allowed lately. “Most of the land at this point is open access, with open bleachers,” he said. “There are many”. of groups that can have games with thousands of socially remote people who are not allowed, and yet cinemas are open. It’s silly. “

It’s a shared vision of the English football landscape. This week, the diverse government of the game, which added the Premier League and the Football Association, which governs the game in England, filed a petition to inspire the government to its regulations and allow enthusiasts to return to elite matches, as happened in Germany, France and the Netherlands.

They that football, and the game in general, is maintained while other sectors can reopen, and that the rules, as they stand, do not make sense.

A Walthamstow story would possibly give weight to this argument. “Police officers participated in one of our games at home,” Perkins said. Police had won reports that football enthusiasts had been seen in greater numbers than allowed in the area.

Fearing that enthusiasts would head to Leyton Orient, the nearest “elite” team, they were sent to investigate. This, after all, would have been illegal. ” But when they found out they were coming to look at us, they told us everything. “Well, ” said Perkins. ” They looked around and told us we were doing a smart task, making sure everyone was at a social distance. “

Ad