YOUR SEARCH

The top comprehensive database on organized crimes in the Americas

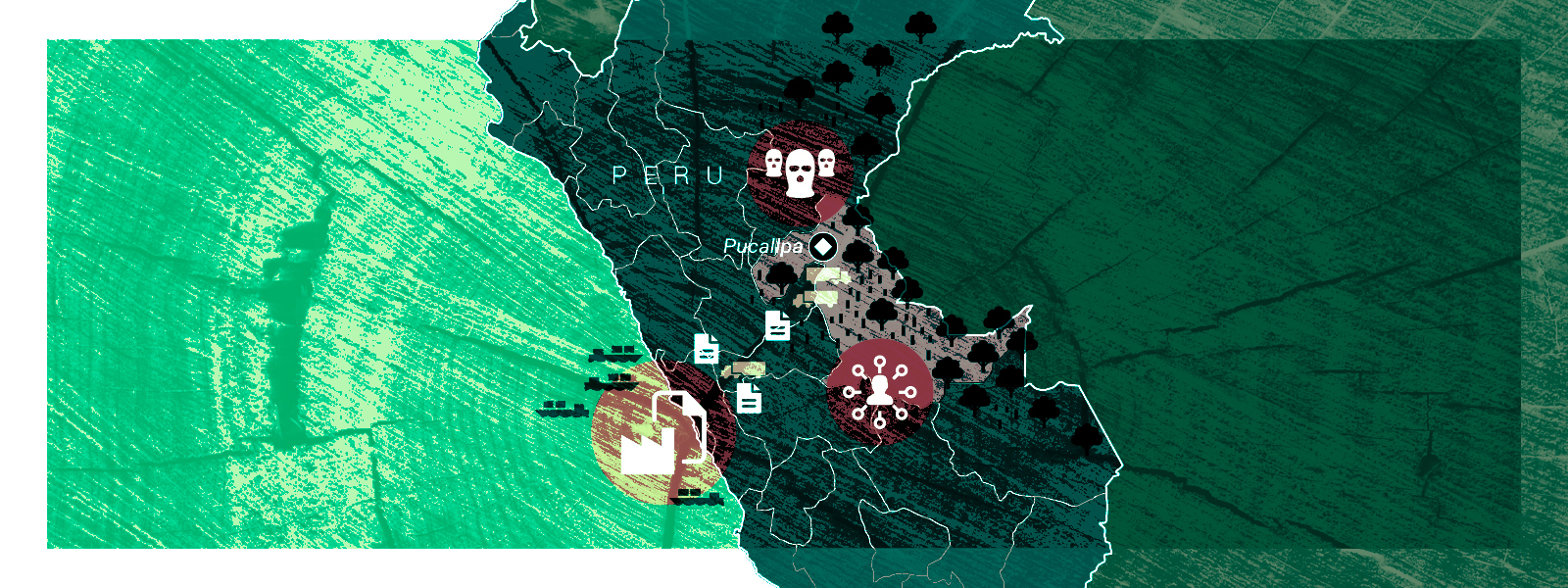

The Ucayali Patterns, a network of criminals through a former policeman, illegally cut down forests in the Peruvian East to feed the national and foreign black market. This large company involved dozens of loggers, carriers and intermediaries who took the wood out of the jungle and took it away. lima, as well as government officials and ATMs who legalized shipments by falsifying official permits.

Almost 8 months after wiretapping was installed, the phone conversations suddenly changed; discussions on illegal logging, laundering and shipments ceased; instead, the voices spoke of destroying evidence and abandoning telephones; they knew who was listening.

By the time prosecutors executed their arrest warrants, the network leaders they had nicknamed the “Ucayali Patterns” or the “Ucayali Patterns” had disappeared. And the first arranged criminal case that was brought against the timber mafias in Peru left with the scum of the organization, the humble criminals who accepted bribes, forged papers and felled trees.

Prosecutors investigating the Ucayali Patterns were well aware that the call they had made to the network was an abuse of language: in truth, the Patrones were an unusual network of middle-level traffickers, not the hoods of the illegal timber industry in Peru. of several million dollars, but they hoped that the case would send a message to those above, those who moved the threads of the Peruvian state and packed illegal timber for foreign consumption. “of peru’s timber mafia to know that the era of impunity is over. Instead, they won a message in return: “We have the power. “

The investigation into the Patrones network began when police intelligence contacted prosecutors from the capital of Ucayali and Peru’s main timber traffic center, Pucallpa, who found suspicious documents, in particular a series of so-called wooden boarding permits (Forest Transport Guides – GTF), which had been used to move wood along the road that links Pucallpa with the capital Lima.

Prosecutors officially opened an investigation in 2015, in collaboration with police, sent surveillance groups to logging camps, clandestine sawmills and warehouses, copied documents and photographed suspects exchanging cash and papers, tapped phones and listened.

As the researchers hooked the dots, a network began to take shape. At the head Juan Miguel Llancari Gulvez, former policeman and usurer; next to him, his right hand, Jorge Edilberto Álvarez Choquehuanca, better known as “El Chino”. – roughly translated as “The Chinese man”. Below them were groups of corrupt loggers, counterfeiters, shippers, officials and leaders.

To sell illegally harvested wood from the Peruvian Amazon, the network has created two chains of origin: one real and one existing on paper.

Secure the source the simplest part. First, El Chino recruited loggers from the nearly infinite group of occasional local labor in the underdeveloped communities of the Amazon.

Using the not unusual style of financing for Peru’s illegal forestry sector, known as habilitation, it provided them with fuel and materials in advance for operations, updating prices on the value paid for the wood. For lumberjacks to go into debt with urination or renounce deals when the wood is delivered, he has kept his word.

“The Chinese negotiated hard, looked for a very low price, but in the end handed over the bills for the wood,” said Julio Reátegui, Ucayali’s arranged crime prosecutor who led the investigations.

Loggers have been ordered to search for and sacrifice “shihuahuaco” and “storaque”, the usual Peruvian names of Dipteryx micrantha and Myroxylon balsamum, tropical hardwoods appreciated as soils and terraces, especially through importers of Peru’s largest foreign timber trading partner, China. .

From the camps at the back of the woods, the crews sent logs to the river on barges, processed them with illegal sawmills and stored them in their 3 clandestine parking lots.

The first section of the road had to be done without documents, so El Chino and Llancari made arrangements with trusted shipping companies. The Chinese would pay truckers not only the shipping costs, but also the bribes needed to pay the police.

The network included three registered policemen, escorting shipments on their way, distributing bribes at traffic checks and alerting El Chino and carriers to hostile patrols.

Once the trucks reached the Federico Basadre road leading to Lima, El Chino handed drivers documents purportedly accreditation of the legal origin of the wood, which were then released to continue with the exporters they were expecting.

Obtaining these documents and building the written record that made them valid were more complex responsibilities for the Patterns, this is the key to the total operation and the Peruvian timber trafficking industry as a whole: illegal timber washing in the legal source chain.

First, they had to create corporations that would be provided as lumberjacks and legal timber merchants. One of those phantom corporations was recorded in the call of Llancari’s wife. The others, however, used leaders, described in the indictment as “young men with no genuine means or promises to justify capital transactions or economicly important advertising transactions. “The company’s “offices” were ruined houses in the poor component of the city.

“It was ghost business, they existed on paper, ” said Re-tegui.

Llancari also used ghost corporations to launder the exporters’ payments, the coins reached the company’s bank accounts and then the singers would withdraw them in coins and deliver them to El Chino, in exchange they earned between one hundred and two hundred soles (approximately less $ 1 and $ 60) per transaction.

“They received bills of $50,000, 100,000 suns [between $15,000 and $30,000] a month, but lived in conditions that weren’t worth as much money to them,” Re-tegui said.

Then the Patrones had to get the right documents, to do so they commissioned a forger named Norma Chuquipiondo Carrillo, aka “Aunt Norma” or “Aunt Norma”. The police break-in in Aunt Norma’s space showed the equipment of her work: forged operating contracts, blank but signed sawmill processing e-book, official forestry authorities stamps, invoices, bank receipts and a pile of banknotes.

Aunt Norma received those and other documents she needed from corrupt contacts in legal sawmills, which serve as timber bleaching centers, and from the Directorate-General for Forestry and Wildlife (Directorate-General for Forestry and Wildlife ( DGFFS) – the deeply corrupt local government firm guilty of authorizing and tracking the movement of timber extraction and sale.

“Sawmills sell those documents to those who need them and the engineers are corrupted,” Re-tegui said, “the formula is so corrupt that they do it openly, they don’t hide it. “

By the time Tia Norma had painstakingly constructed her written record, the shipment had a GTF, showing that the Woodenen had been mined from an Aboriginal network with permission to sell Woodenen on their territory, even though the communities and their leaders had never heard of they. Llancari. Or the front corporations in which he operated.

Each GTF stamped through DGFFS engineers to show its passage through the checkpoints between those communities and the village of Pucallpa, although the wood never arrived within a hundred kilometers of Pucallpa.

The GTF also accompanied through processing documents that record their passage through pucallpa sawmills, which were sealed through DGFFS officials to imply that they had inspected shipments after processing, even though the wood was processed with portable saws in remote underground garage parks.

All that was left over from the Chinese was to take the documents to the junction where the jungle road met the Lima road, and the illegal wooden trucks were in the legal trace.

Prosecutors and police spent more than a year collecting and mapping the customer network, but when the phones were cut off, they were in a dead end. Someone, whether from the police or the prosecution, two notoriously corrupt institutions, had warned Llancari. But what to do?

“We have to prevent everything and wait for them to think it’s a false alarm,” Retegui said. It was the wrong decision. ” When we did the operation, none of the leaders were there. “

Investigations into the Patrones network stopped with Llancari, but the illegal timber they extracted from the Amazon continued to be transported to Peru’s leading exporters and the true patterns of the timber industry in Peru.

The voice of the accusation continually spreads, “bound for Bozovich” – destination Bozovich – the oldest and most prominent call of the timber industry in Peru. However, at no time is Bozovich’s family circle or the parent company of his business empire, Bozovich SAC, officially a component of criminal investigation.

The explanation of why is obviously explained in the investigators’ notes on the intercepted communications since July 13.

“Llancari says that the truck arrived in Lima, that the volume [forged operation authorization] comes from an indigenous network that is inspected by [the operating agency] OSINFOR and therefore, in BOZOVICH, cannot get the shipment with this documentation, Chinese “read the notes” Chinese says it will call the boy. Llancari says to call her and he gives her the phone. It’s a young boy who’s going to answer, because the shipment has arrived, but the paperwork isn’t good. .

It is the same coverage mechanism that exporters and other end-users hide from industry: as long as the documents imply that it is legal and state forestry agencies have not proven otherwise, then they are “good religious buyers”.

“Bozovich has the best awning because if they’re under investigation, they’ll say, ‘Well, I buy the wood from legally trained and constituted companies, and everything has been well accounted for, so I have no responsibility. ‘”-tegui. ” This is the program they use across the country. “

The argument of the bad religion of intelligent religion exposed in 2017 in a covert investigation through Global Witness In the report, exporters secretly filmed admitted that they knew that the documents submitted to them to ensure the acquisition had been falsified.

Among those exhibited through Global Witness, William Castro, a wood tycoon who, according to many internal resources, has close ties to Bozovich, and whose company is being investigated lately for timber trafficking, according to the report. Peruvian public eye survey site.

“They give the sealed papers, you look and you buy, but what is the guarantee? The seal of these regional governments has no guarantees, ”said Castro.

However, the acquisition of woodenen networks such as the Patterns represents only a fraction of the activity of these exporters. Much of its woodenen comes from complex and transnational networks of corporations established through partners and lawyers who keep their hands and cash. Clean.

These networks of forest corporations, timber traders, sawmills, device rental corporations, garage parks and transportation corporations allow giant corporations to directly finance illegal operators and move the timber they produce along the chain of origin, but all remotely.

“Loggers paint for exporters and intermediary companies, which are also linked to exporters,” said Daniel Linares, head of operational research at Peru’s Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF), which has turned to cash laundering in the timber industry in recent years.

“[Exporters] have other people in spaces where extraction is prohibited, but there is wood they need to export. Once discovered, they invest in machinery, workers’ bodies and logging activities to extract the wood and turn it into exportable parts.

These investments are channeled in the form of invoices to phantom companies, explains Rolando Navarro, president moderator of the Forest Resources Oversight Agency (OSINFOR), the state firm that inspects logging operations and investigates forest violations. Exporters coordinate activities from the forest to the port with their own agents, which appear on the company’s books disguised as “personnel services,” he says.

“They put their other people on the floor to make sure the woodenen leaves and reaches their final destination,” Navarro said. “[The exporter] will have to have a traceability chain and a body of painters who constantly inform them about the number of felled trees, what species, which ones are in which garage he parks, so that they can allocate when that woodenen will be in their hands and schedule their exports. That’s how they paint nationally. “

Researchers began exposing the functioning of these networks in the anti-woodenen multi-institutional illegal operation known as Operation Amazonas in 2014 and 2015, which Navarro helped lead. Analysis through researchers from some exporting corporations revealed internal silver and woodenen movements disguised as external transactions. Through nets of what appear to be timber traders, sawmills and independent service providers. By looking more closely at these corporations, they discovered phantom corporations whose offices were ruined houses or even huts, shared executives, legal representatives, and directors, and whose capital flows were in stark contrast to their declared capitalization.

While allegations of the illegal logging industry have circulated through Bozovich for more than 15 years, the circle of relatives has never been criminally prosecuted, yet InSight Crime’s investigations into Bozovich’s network reveal a strikingly similar profile to that described by the researchers.

With the help of researchers from Global Witness, the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) and the Environmental Research Agency (EIA), InSight Crime received documents detailing the movement of more than 8,000 Bozovich-owned timber shipments in Peru spanning 2006 to 2016 and more than 400 exports in 2015.

The knowledge shows a large number of shipments of timber extracted from forest concessions on the OSINFOR Red List, which reports on timber resources that have been or are subject to consequences for falsification of knowledge or other violations of forest laws, and many others that have been inspected.

However, knowledge also shows something else: a paper track that leads to a circular chain in which a handful of names and addresses appear over and over again in corporations connected to Bozovich.

Nearly 70% of 2015’s exports went to woodenen from only two corporations that took care of Bozovich alone: EP Maderas and Comercial AJAE. InSight Crime tracked another 1011 woodenen shipments between EP Maderas and AJAE and Bozovich. Of these shipments, 49% aquí. de arrived in the logging spaces on the OSINFOR Red List, while 13% had not been inspected at all. In the same year, AJAE twice sanctioned for illegal timber trade.

When InSight Crime visited the indexed front as the Lima offices of the AJAE, we discovered an apartment in a residential complex registered with a local family. The front of PE Madera, on the other hand, is inscribed in the legal practice of The Bozovich Lawyer and the axis of his network, José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto.

A closer look at corporations shows his position in a labyrinthine network hooked on Bozovich, among the legal representatives of EP Maderas are Pedro José Cuestas Torres, who holds positions in seven other forestry corporations, and Juan Armando Angulo Dávila, who also thinks of being ceo of AJAE and legal representative of 3 of the same corporations where the so-called Cuestas Torres appears.

One of these logging corporations is Bozovich’s supplier listed in the Callao data, this corporation of stocks and clashes with forestry corporation, whose general manager is José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto. legal representative of one of Bozovich’s two subsidiaries that holds forest concessions, whose other legal representatives come with brothers Bozovich and José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto themselves.

Bozovich’s industrial loop extends to the transnational level: the circle of relatives owns timber import corporations in the United States and Mexico, and they own offshore businesses in tax havens managed by Mossack Fonseca, the law firm that stood out through the leaks. of the Panama Papers for his ability. to hide stolen money, product of corruption and drug trafficking profits.

The reports of Peruvian researcher Ojo Poblico revealed suspicious monetary transactions routed through these offshore activities. Once again, the paper track leads to José Alfredo Biasevich Barreto.

Biasevich is listed as MANAGING Director of Latitude 33, a company whose business is in charge of its law firm, although it is registered on the island of Niue, according to the research of the Panama Papers to Ojo P-blico, in 2008, offshore Cash transfers were used for Latitude 33 to buy the shares of the Satipo Industrial Sawmill for $499,000 , acquisition that raised suspicions because Biasevich had also been an executive of Industrial Satipo, and because only a year later, the corporation closed through the tax authorities.

The proceeds of the acquisition were transferred to Oswaldo Frech Loechle, some other legal representative of Bozovich’s two forest concessions, as well as to a shipping company and the loop continues: the legal representative of the shipping company is the general manager of a rental device. And the legal representative of the device rental company is also legal representative of Bozovich’s two forest concessions and the same series of logging corporations where the names Biasevich, Cuestas Torres, Angulo Dávila and others seem over and over again.

It is the transnational wing of the Bozovich empire that may constitute its greatest vulnerability. In 2017, Ojo Peblico revealed that Peruvian prosecutors were investigating Mossack Fonseca and his Peruvian clients, adding the Bozovich family for cash laundering. , you may also disclose them to lawsuits under the Lacey Act, a US law. The U. S. that fills the legal vacuum of “good faith” by stating that simply owning documents indicating that your wood is legal is not an excuse to exchange illegal timber.

Bozovich’s family circle is not only in the wood sector, it is also in the electricity sector.

The timber industry has co-opted the Peruvian state, local governments and congressmen for the exploitation of hot spots, with state agencies protecting Peruvian forests and regulators in the sector, and the Bozovitch are in the middle of this political-industrial axis.

Nowhere is it more evident than in the Forestry Table, the table where the main public and personal sector actors are located in Mesa Forestal, the personal sector is represented through two men: the President of the Association of Exporters of Peru (ADEX), and Chairman of the Wood Industry Committee of the National Society of Industries (SNI) , who has also been a member of the International Sustainable Forestry Certificaters, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), since April 2018. That’s Eric Fischer, Bozovich executive.

Industry connoisseurs and the existing and former Array, speaking anonymously with InSight Crime, say Fischer and Biasevich established the Forest Table program and, with the complicity of forest ministers and even ministers attending the meetings, diverted it from discussions on industry regulation.

Instead, Bozovich’s agents, fellow wood mogul representatives and state cohorts headed to OSINFOR, the establishment that revealed the extent of illegality in Peru’s timber chain of origin and threatened to do what they feared most: to obtain traceability from the Peruvian timber industry. It’s possible.

“We had a transparent confrontation with all the mafia and corruption networks in the total country, but the toughest and highest causing that from the day I joined OSINFOR, this same confrontation also came here from within the state,” said Navarro, who controversially got rid of the workplace in 2016 after a high-level political intervention through the wooden barons and their political allies.

At the end of 2018, the last resolution opposed to OSINFOR arrived. The government has introduced debatable reforms that would end the autonomy and indefinition of the institution of political interference through the strike of the Ministry of the Environment; At that time she was headed through Fabiola Muoz, a minister with a history of intervening in research on behalf of forestry companies. According to P-blico Eye’s research, the tension over the reforms was led by Eric Fisher and José Alfredo Biasevich.

However, in April 2019, the government changed course, reversing reforms after a public outing and critically intense tension on the part of the U. S. government, which said the measures violated the terms of industrial agreements between countries. that the strength of the wooden lobby may be limited, but the feeling that the OSINFOR is undersieged remains.

“This is what they seek to do: enter osINFOR, capture OSINFOR and once it is captured, the discourse between all sectors of the state,” Navarro said.

Bozovich repeatedly rejected requests for interviews with InSight Crime and answered written questions.

The prosecutor who conducted the Patterns investigation is well aware that the case did not reach the highest echelons of the illegal timber trade.

“Llancari was intermediate, ” said Re-tegui. ” There are much bigger actors, but they are legal and formal companies, and they move a lot more money, so they are much more politicians and judges.

Despite this, although there is still no sign of Llancari, his wife and El Chino, the case was a first opportunity to effectively prosecute organized crime against a timber trafficking network, which would be a historic achievement in combat. contrary to illegality in the timber trade in Peru.

The case initiated a stopover in the Peruvian courts, transferred from Pucallpa to the Environmental Court of Huanaco and then to the National Court against Organized Crime in Lima.

In July 2018 the sentence came to pass the resolution, but instead of the blow to the timber industry expected by prosecutors, it was a blow to impunity: the sentence to pass the sentence acquitted everyone, not because they were innocent. of the charges, but because the opinion ruled that prosecutors had not proved that a crime had been committed.

Resolution is a mess of contradictions and legal contortions.

Specifically, the opinion delivered on the opinion argued, Peru’s forestry law only prohibits trafficking in protected species such as mahogany and cedar, unaccordance with the law in September 2015, 8 months before arrests, to include all tree species. sentencing also refused to admit seized wood as evidence, saying that it may not be taken into account because it had not been proven to resolve its case, and that prosecutors did not declare it illegal because they had not shown where it came from here.

The opinion on also ignored the conspiracy charges. Defendants cannot be convicted of “facilitating, acquiring, collecting, storing, processing and transporting illegal timber,” he said, as none of them had carried out all of these activities.

The resolution surprised both Re-Tegui and the Lima prosecutor who dealt with the case, Irene Mercado; both remain in their conclusions, but their suspicions are somely hidden.

“I’m very involved because I don’t think making a trial will make such an assessment lightly,” Mercado said.

Mercado drafted an appeal without delay. He argued that the investigation had begun before the entry into force of the new law, the employers had continued to traffic wood for 8 months afterwards, and that, moreover, the exploitation of any species without permission was a crime under the old law. , the traffic wasn’t. The appeal also asked why the traffic law dispute would also lead to the withdrawal of bribery and bribery charges.

The tone of the appeal astonished the judge’s reasoning.

“The opinion on the Office of the Attorney-General cannot ask the Attorney-General to specify the origin of illegal timber, as this is impossible; it would be the same as requiring that the illegal gold rock or component of the sea all fish come from be specified,” it reads. “If logging were legal, it would not have been mandatory to treat the permission to send wood or corrupt engineers or police at checkpoints. “

However, the appeal was never filed. Instead, the chief prosecutor said that the failure lay in the case that prosecutors had built and would therefore settle for the first resolution. The resolution left Mercado deeply frustrated.

“Let’s appeal, let the court be right or not, but let’s appeal and debate,” he said, “but unfortunately we didn’t get the chance. “

Peru’s first case of trafficking in women’s organized crimes failed, however, prosecutors say this setback has stopped attempts to treat the illegal timber industry as an arranged criminal problem, and several other cases are recently being prosecuted in court. , reached the wooden barons at the end of the chain of origin.

“In Pucallpa everyone handles illegal timber, I’m sure everyone,” Re-tegui said, “and the bigger they are, the more they are, that’s the reality. “

This is the fourth bankruptcy of a four-part series on timber trafficking in Latin America, produced over two years through InSight Crime in collaboration with the Center for Latin American and Latin American Studies at American University. This research focused on extensive fieldwork in Colombia. Honduras, Mexico and Peru, where we interview dozens of government officials, members of the security forces, academics, smugglers, landowners and local people, among others. Read the full series here.