“The spirit of the 1993 team will be present in Zambia. “

Former Zambia captain Kalusha Bwalya reflects on the day that replaced his life forever.

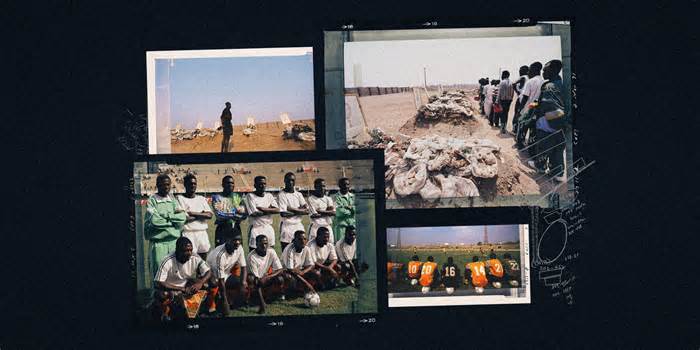

On April 27, 1993, a military plane carrying 18 of his teammates and coach to a World Cup qualifier against Senegal crashed shortly after refueling in Gabon. The other 30 people on board were killed.

Advertisement

Bwalya would have been on the plane, too, but for the fact that he was playing for PSV Eindhoven at the time. Being based in the Netherlands meant he made his own way to the match from Europe and ultimately saved his life — although it did not spare him from crushing, numbing grief.

“You can’t believe the whole team you play with isn’t there anymore,” Bwalya told The Athletic. “It didn’t feel real. “

Zambian football could have been broken by the dreadful events of that day nearly 31 years ago. Instead, in the year that followed, a new national team — captained by Bwalya — came within one match of reaching the 1994 World Cup and also made the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) final.

Against all odds, an underrated Zambian team went one step further and won the 2012 AFCON final in Libreville, the Gabonese city where the doomed plane carrying the 1993 team crashed minutes after takeoff. A tragic story had come full circle.

Now, as the team known as The Copper Bullets prepares (Wednesday) for their first AFCON game since 2015, here’s the story of that plane crash and the team’s enduring legacy in their country and beyond.

It has now been forgotten, amid the trauma of how its story ended, but that 1993 Zambian team was widely hailed as one of the most productive the country has ever produced.

They had real hopes of reaching the World Cup final for the first time and also winning the AFCON trophy. Just two days before the plane crash, the team had travelled to Mauritius for an AFCON qualifier, beating their hosts 3-0 thanks to Kelvin. Mutale, a talented young striker, who scored a hat-trick.

Bwalya missed that match but planned to link up with the squad for their next game, an important World Cup qualifier against Senegal in Dakar, that county’s capital city.

Advertising

That convention took place.

The squadron had boarded a twin-engine De Havilland Canada DHC-5D Buffalo military aircraft and was scheduled to fly to Senegal, West Africa, via stopovers in Congo, Gabon and Ivory Coast.

After its second stop to refuel in Libreville, Gabon’s capital, it took off from Leon-Mba International Airport. Two minutes later, it crashed just 2km (a little over a mile) from the coast, killing all five crew and the 25 passengers. According to the accident report, which was finally released in 2003, the right engine caught fire but the pilot shut down the still-functioning left engine, meaning the plane plunged into the Atlantic Ocean.

Gabon sent foot soldiers to search for the bodies, but 24 of the 30 were recovered and thirteen were known for sure – a complicated task entrusted to Patrick Kangwa, vice-chairman of the Zambia Football Association’s technical committee.

Following the tragedy, Zambia’s President Frederick Chiluba, who was on a state visit to Uganda when he learnt the news, announced a week-long period of national mourning and a state funeral for the players, who were all later buried in ‘Heroes Acre’ close to the Independence Stadium, in capital city Lusaka. It was not until May 2002, after a lengthy court battle, that families were awarded compensation of $4million (£3.1m).

Bwalya is one of four Zambian club players from Europe, along with Charles Musonda, Johnson Bwalya (unrelated) and Bennett Mulwanda Simfukwe, who made their own way to the Senegal match. I was running in the morning on PSV’s educational pitch in Eindhoven. when he won a call from the treasurer of the Zambia Football Federation.

“He said, ‘You have to delay your flight tomorrow. ‘ I said, ‘Why?’He replied, “Because there was an accident. ” He said he thought there were victims.

Advertising

Bwalya then recalled watching the news and seeing a BBC report claiming that all his teammates heading to Senegal had died in a plane crash and that there were no survivors. “At the time, you don’t think about it much,” he says. You just think it’s a mistake. There was a lot of denial on the first day.

He spent the rest of that day on the phone frantically trying to piece together what exactly had happened while worried family and friends called to find out if he was on the flight.

Back at PSV’s training ground the following day, he remembered his club colleagues trying to protect him by hiding the newspapers, with stories of the crash.

The next day, a Friday, Bwalya flew to Zambia via the UK. He said: “When we were taking off from London, the pilot said I should go to the front of the plane in the cockpit, so I could see the take-off and landing because he thought I would be very nervous to fly. I was in the cockpit in London when we took off.

“When I arrived in Zambia, every time other people saw you, they cried. On Saturday, the plane that had left for Gabon returned to retrieve all the bodies, that is, the other 30 people who died. When that plane came here and landed, it was the first time it hit me and I knew I would never see the kids again.

Musonda was also playing in Europe, for Anderlecht in Belgium’s capital Brussels. He was desperate to play in that World Cup qualifier against Senegal but had a longstanding right knee injury and was told he couldn’t join up with the national team by the club’s owner.

His son, Charles Jnr, who played for Chelsea’s youth team before a knee injury sidelined him for three years, said: “My dad was furious (he wasn’t allowed to play in the game). Two days later, the plane crashed, if he was on the plane, I wouldn’t be here.

Some players had even more fortunate escapes.

Martin Mwamba, the third goalkeeper, was part of the squad against Mauritius before being ruled out for Senegal. He had had breakfast with the Zambian team before setting off on the long adventure to the northwest. It was his wife, in tears, who broke the news.

Advertising

“I turned on the radio and it was playing everywhere,” he said. “I was very shocked. ” His circle of relatives had assumed that he had passed away and opened his home to the bereaved.

“It was very difficult for me to get out of this tragedy. It took me two months to start working.

Others weren’t so lucky. David “Efford” Chabala, the first-choice caregiver, was one of 30 who died, leaving behind four children and a wife, Joyce, who was pregnant with twins.

One of his sons, Freeman — who was seven when his father was killed, and subsequently became a professional footballer — told FIFA.com: “I didn’t understand what it was. And anybody that I asked what it meant… I was only told, ‘Your dad is not coming back’. And I kept on wondering why Dad would decide not to come back. It was something I had to wrestle with for a very long time.”

Zambia mourned not only the tragic loss of those young men killed too soon, but also the loss of talented footballers who were on the verge of making history.

The country had at times threatened its most powerful regional rivals at the Africa Cup of Nations, reaching the final in 1974, after losing to Zaire after a replay, but never won the tournament or qualified for a World Cup.

This group, however, was considered special, a combination of exciting young talents such as Mutale, a Manchester United fan who had taken his foreign tally to 14 goals in thirteen games with that hat-trick against Mauritius, and older players who had great success. Tournament experience, having competed in combination at the 1988 Summer Olympics in South Korea.

They were guided by their new coach, Godfrey Chitalu, widely identified as one of the country’s greatest players of all time. Chitalu, who had replaced Samuel “Zoom” Ndhlovu months earlier, was also killed in the crash.

“The team is built on a solid foundation,” Bwalya said. “David Chabala was a goalkeeper, one of the most productive to ever come out of Zambia and very influential. Wisdom Chansa was a very intelligent friend, another very vital player, who played in the number 8 position. We won one of the first tournaments in Zambia with the U20 team.

Advertisement

“Derby Makinka was a midfielder of the highest calibre: he could defend and shoot with his left and right foot. Eston Mulenga was a very solid centre-half. We had young players that came in, like Patrick Banda and Mutale, who were lethal up front. They didn’t play many games but were brilliant talents.”

A frightening aspect of the story is that prior to the crash, Zambian players had raised concerns about the unreliability of the green-camouflaged Buffalo army plane.

“There’s been a problem,” Bwalya said. The guys were like, ‘This plane is going to kill us. ‘The deal didn’t have a lot of cash to take the team on a publicity flight, so the simplest way was to request an Air Force plane.

In an earlier match, in a World Cup qualifier they lost 2-0 in Madagascar in December 1992, they had stopped to refuel in Malawi. After hours stranded on the tarmac due to a pay dispute, they took off again.

On the four-hour adventure over the Indian Ocean from the African continent, the pilot insisted that players wear life jackets.

While the shocking events of April 1993 seem remarkable three decades later, what happened next defied belief: a new Zambian team recovered.

“When I arrived in Zambia for the funeral and saw all the bodies, I didn’t think Zambia would be able to compete at a decent level, because you feel like you can’t lose a generation of players and then start over,” Bwalya said. But that’s a credit to the coaches, Roald Poulsen and Ian Porterfield, and everyone else involved. When you think about it, the team may have come out of nowhere.

To start with, the players met for a six-week training camp in Denmark under Poulsen, a 44-year-old whose main claim to fame had been winning the Danish title with Odense five years before and whose services had been offered to Zambia by the country’s football association.

Advertisement

Zambia played matches against groups from other levels of the Danish league formula before a World Cup qualifier against Morocco for a place in the 1994 World Cup final in the United States.

“About three weeks after the disaster, I received calls from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Danish Football Association,” Poulsen said, “asking if they could help me for six weeks in Denmark. Maybe we’ll see that it’s going to be like that. “

President Chiluba convinced Bwalya to sign up for Denmark’s new team.

“The president called me and said: ‘Skipper, we will have to continue, otherwise the death of our heroes will be in vain. ‘ We cannot allow our country to sink like this. You have to be there to motivate the boys. “If other people see you, they will feel encouraged to continue. ” So I said, “Okay, I’ll do my best. “

Just 67 days after the air disaster, on July 4, this new Zambian team bounced back to beat Morocco 2-1 in Lusaka, thanks to a Bwalya free-kick. Poulsen later said it was “the greatest emotional adjustment I’ve ever experienced. “

However, after a draw and a consecutive win against Senegal, they missed the USA 94 match following a 1-0 loss in their last qualifying match, the second leg against Morocco in October.

But, again, this team were not finished: the next year, Zambia reached the AFCON final in Tunisia under Porterfield, a Scottish former manager of clubs including Chelsea, Sheffield United and Aberdeen.

They scored the first goal of that final, but lost 2-1 to a Nigerian team that included Jay-Jay Okocha, Sunday Oliseh and Finidi George. Porterfield, who died of cancer in 2007, was later released from Zambia.

Bwalya said: “When you look at yourself (the rest of your team) and only see new faces, not the ones you’ve been looking at for 10 years, it’s a deceptive feeling. It hits you. But we’ll have to pay tribute to the boys who put themselves in the shoes of fallen heroes.

Against all odds, Zambia did better and were crowned African champions in 2012, under the guidance of Frenchman Hervé Renard.

Precisely, this last rival from Côte d’Ivoire was located in Libreville to complete a story, as the team laid flowers on the beach of La Sablière, near the site of the accident, in memory of those who died there 19 years earlier.

Advertisement

In a previous interview with The Athletic, Renard said: “Perhaps the most productive Zambian team of all time died in that twist of fate in 1993. We wanted to do it for the players that Zambia lost, but also for Kalusha Bwalya. “And for all the people of Zambia. Es a legal responsibility to play for the memory of the people.

“Emotionally, it was very vital for us. The spirit of those players was something I don’t think I’d find anywhere else. When I returned to Zambia later, other people told me, “You put us on the map. “”They’re very proud of that 2012 team. That’s the right word: special.

Bwalya, who was by then president of the Zambia FA, recalled: “It was a sunny day but the clouds turned dark and there was lightning, so everybody was moved by the whole ceremony.

“It’s like there’s a meeting between the old team and the new team. You might feel in the air that Zambia is another team between the visit to Sabliere Beach and the return to the hotel. The old team provided the team when we played (the final) against Ivory Coast. The rest is history.

There was certainly an air of destiny about the manner of Zambia’s triumph in the final. Chelsea striker Didier Drogba missed a penalty in the second half with the score still 0-0, before the game went to penalties.

After a total of 18 goals on target, and with the nerves of a country on edge, Zambia managed to win their first AFCON title, a title that even their warring parties may want.

“In Africa, we strongly support things like this when it comes to faith and culture and, for us, it was written in the stars for them,” said Sol Bamba, a member of the Ivory Coast team that day, who played in the United Kingdom. for several years. Leeds United, Cardiff City and others. “After the sadness and sadness between us, we talked about it and said, “Maybe it’s not a bad thing that Zambia, despite everything, won. “

Now it’s up to the 2024 team, which has Leicester City’s Patson Daka as its star player, to write its own script.

Their organizational schedule begins against the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Wednesday) and, although expectations are not high, the events of 1993 ensure that any Zambian team that reaches the top spot in a primary tournament will not lack motivation.

Ad

“We were an exciting team and this is just the beginning,” Musonda Sr. said. “The legacy of this team will live forever. I hope the new team can challenge and bring honors to Zambia again.

(Top photos: Simon Bruty/Allsport, Neal Simpson/EMPICS, both via Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)