What would it be like to be stranded on a desert island and see, over the years, go from 20 to 30 boats stopping?

On October 16, 1847, an organization of sailors from HMS Rattlesnake landed in Cape York, Queensland, in northeastern Australia, and encountered an Aboriginal on the beach without looking at it for a moment.

They turned around when she spoke to them in English. “I’m a white woman, why are you leaving me?” She.

After a closer examination of their “dirty and depressing appearance,” they learned that they were chasing someone who had been trapped here for some time. What they didn’t appreciate was their concern that the other Aboriginal people he had fled from seemed to have decided at any moment to get her back.

This unexpected incident was recorded through the ship’s naturalist, John MacGillivray, 26, whose task was to document flora and fauna, with hardly anyone who did not wear clothing for a narrow strip of leaves on the front, his skin tanned and blistered through the sun and who was not only British but arrived here from the same component of Scotland as MacGillivray – Aberdeen.

It was a reconnaissance project that HMS Rattlesnake, commanded through Captain Owen Stanley, had been sent through the Admiralty, whose instructions, ironically, included: “You will be careful never to be surprised.”

They had to locate an address around the summit of Australia, across the Torres Strait, for the return ships. Accompanied through the Tsar, and dressed with 180 officers and men, the two ships had sailed from Plymouth on 11 December 1846. They were also told to take 50,000 euros (much more than 1 million today) in the Cape of Good Hope and 15,000 euros of treasure. to Mauritius, a British colony since 1810 when it was recovered from the French.

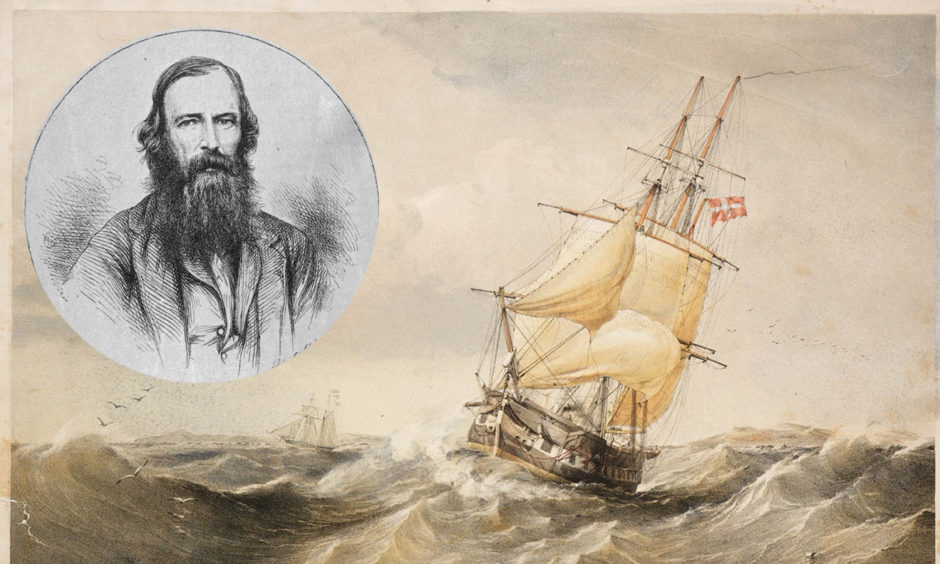

John MacGillivray was born on 18 December 1821 in Aberdeen, the eldest of 12 siblings. His father, William, a prominent British ornithologist and Regius professor of herbal history at Marischal College in Aberdeen.

Studying medicine in Edinburgh, and before graduating, MacGillivray named him through the thirteenth Earl of Derthrough as a naturalist with HMS Fly, in which he spent three years travelling off the coast of Australia and New Guinea.

His account of the occasions of his adventure now, HMS Rattlesnake’s Account of the Journey, was published in 1852. After crossing the Atlantic, MacGillivray witnessed slavery in Rio despite its abolition in 1835: “The frequency of iron collars around the neck, and even the tin masks, which hide the waning component of the face and constantly with a padlock, seem to imply excessive brutality.

Arriving in Hobart Town in June 1847, they sailed along the east coast of Australia and in August contacted other Aborigines on the 19-4 mile sandy hill called Moreton Island, off the southeast queensland coast. His encounter with the Aborigines shows how delicately balanced (and potentially volatile) quotations between two completely different cultures at the time may simply be: “Although these natives had a wonderful relationship with Europeans,” MacGillivray wrote, referring to “friendly communication”between them,” some of those who came on board may not be persuaded to pass underneath; and a strong guy (an eye, as he called himself) trembled with concern when I grabbed him by the arm to bring him down.

One day, his dispatch attacked: “His first act of throwing barking in the cockpit,” he wrote, “and when the captain and one of the team rushed to the deck in a state of confusion, they were knocked down without delay. head with boomers and became insensitive, but another sailor came and chased the Aborigines with a sword.

MacGillivray has documented 41 marine species in the past unknown to science.

While fishing for mullet and bream, they also encountered the ultimate predator: “Huge sharks seemed to be common. One day we caught two, and while the first catch hung below the stern of the ship, others repeated attacks opposed to it, partially lifting their heads out of the water and tearing long strips of flesh before the creature died.

They landed on Eagle Island, named after Captain Cook, who had discovered a giant nest there and wrote: “It was built with sticks on the ground and no less than 8 meters in circumference and 2 feet 8″ (2 m) high,” MacGillivray added. he and Mr. Gould were sure they were “the paintings of the wonderful Australian eagle.”

MacGillivray’s spirit was never far away: “One of the ship’s team members, who was not brain overloaded, picked up a human skull with meat-adhesive parts during his walks.” The sailor had thrown him into the sea even though a European hut with clothing, shoes, tobacco and pieces of whaling had been discovered. Was it some other Robinson Crusoe?

But now she forgot that MacGillivray and the others had met a genuine castaway, Barbara Thomson, 21, who, four or five years earlier, was the only survivor of a shipwreck near Prince’s Island of Wales, on the outskirts of Cape York, after a with her husband in her cutter.

She was about to realize that she had been rescued through the Aborigines in a canoe that took her to another island (Muralug) where one of them, named Boroto, as MacGillivray later wrote in his diary, “he took over her as his component of looting; she was forced to live with him, yet she was well treated by all men, many women, jealous of the attention paid to her, have long manifested more than kindness.

Always heavily guarded through the Aborigines, Barbara used to see boats pass just 3 kilometers away and assumed that the possibility of escape would never come. But when he saw the rattlesnake strapped into a continental bay, the temptation was too great. She convinced her nearest Aboriginal friends to take her to the boat, with MacGillivray writing: “Blacks were gulloles enough for that, as she had been with them for so long and had been treated so well that she didn’t aim to leave them, only she felt a strong preference for seeing whites back and shaking their hands (and) to get axes (and) to get them axes of Array knives , tobacco and other popular items … After landing in the sand bay west of Cape York, he moved rapidly across Evans Bay, as fast as his limp allowed, fearing that blacks would replace their minds; well, she did, because a small organization of men followed her to stop her, but she came too late.

Three of them, those who had rescued her from the shipwreck, were admitted aboard at the request of Barbara, where they won a punch and other gifts. They would have now known that Barbara had just changed the stage and that she had used the same tactics they used against her for years to remain her. But, he actually broke free, would he stay? After all, she had been part of a circle of Aboriginal relatives for a long time. Maybe now he’d replace his brain and stay with them.

British officials didn’t know what to think. If you didn’t hear him speak right away, MacGillivray and the others, who were now probably all fascinated, would have had the option that this white woman, trapped for so long, had simply forgotten how to speak English altogether.

“Asked through Captain Stanley if he would stay with us to accompany the natives … I was so restless … using fragments of English alternating with the Kowrarega language, then … incomprehensible, the deficient creature blushed everywhere, and … . he hit his forehead with his hand, as if he wanted to help sort his scattered thoughts, ” wrote MacGillivray. “Finally … discovered the words: “Lord, I am a Christian, and I prefer to pass to my own friends.”

Boroto allowed to embark with gifts of fish and turtles, however, “after searching in vain through sweet words Array.. to induce him to live with him again, he left the sending angry (and) threatened him, if he Array.. fake woman” on the shore, would cut off her head.

Needless to say, he stayed on the boat, was “temporarily restored (a) his fitness and … even though it all happened to his parents in Sydney.”

The rattlesnake returned to England in 1850, MacGillivary emigrated to Australia in 1864 where, on 6 June 1867, he died of an attack on the center at the age of 45.

One can only wonder if Barbara Thomson has ever visited her huge collection of birds, shells and plants, which still live in places like the British Museum and Kew Herbarium, and has noticed all the other things that had been dragged to the beach. .

For as little as £5.99 per month, you can use all of our content, adding Premium items.