Advertising

Supported by

Critics’ Notebook

In the corridors of power, its functionality worked for a time. Outside, it’s a failure.

By Amanda Hess

Amanda Hess is a general critic covering culture. She first wrote about the complicated performances of Cameo celebrities in 2018.

George Santos was expelled from Congress on a Friday in December. The next business day he announced a new role: that of a kind of clown for hire on Cameo, an application and online page where he presented his personalized videos for fans. At first, he priced the messages at $75 each, but soon charged $200, then $400, and finally $500 each. But last week, the market contracted. The videos dropped to $350 each.

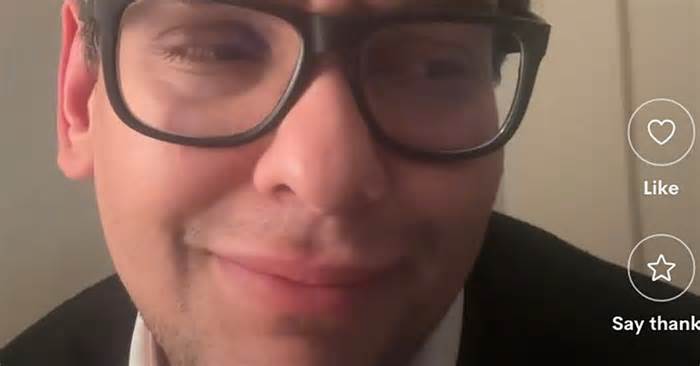

Working on Santos’ Cameo — a TikTok account, @georgiescameos, that collects clips — is a depressing exercise. In a typical ofrenda, you sit on a floor or in a dark van. His face looks glassy from Botox, his eyes looking for the stage. He painfully expresses his condolences and congratulations. He says “kill, my daughter”, he says “kill him”, he says “diva down”. Sometimes he winks at the accusations of fraud that oppose him. End with an airy kiss. Mwah. Cha Ching.

I felt ill watching the videos, not because they enriched a fabulist, but because they are so tedious and flat. There used to be a transgressive appeal to the character of Santos. As he moved erratically through the halls of Congress, his deceptions tarnished the reputation for seriousness of the American government itself. It’s the inadequacy of its ultimate prestige that made it fun. Now that he’s weakened, viral fame doesn’t create any tension for a Santos character. There’s nothing transgressive about a con artist in Cameo.

Santos is right to think that his political downfall had some kind of entertainment value. Bowen Yang took his form several times on “Saturday Night Live” last year, betting him as a languid and pathological goblin. There’s a Mad-Libs quality to Santos, a dizzying coincidence that seemed to be geared toward social media. He said he had suffered family trauma from 9/11 and the Holocaust; that he had worked at Goldman Sachs and “Hannah Montana”; who played competitive volleyball and rescued puppies. (None of this is true. ) As reporters chased him, his erratic on-camera appearances — tripping over his workplace door or inexplicably holding a baby — seemed to clash with the wooden interiors of Congress.

George Santos, who was expelled from Congress, has told so many stories that it can be hard to follow them. We’ve cataloged them, adding key questions about their personal finances, as well as their campaign and fundraising expenses.

We are retrieving the content of the article.

Please allow javascript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Sign in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Advertisement